Lake Effect

May 13, 2012

Text by Nathaniel Reade Photography by Michael Partenio

Rob Dean had a problem. This one, however, didn’t involve a demanding client or rotted sills. It was a problem of design.

Dean is a New Canaan–based architect with graying blond hair, horn-rimmed glasses and a preference for tweed jackets. He had clients in Fairfield County for whom he’d done previous work, an active family with four young kids. They were looking for a vacation retreat not too far away that would provide them with casual relaxation on a lake. They liked what they saw at Lake Waramaug, in Litchfield County. The lake area is so appealing, however—an hour and a half from Greenwich, two hours from Manhattan—that the clients didn’t find many properties for sale, especially with the kind of site they wanted. It had to be at the water’s edge, secluded, with good exposure to sunsets and water views. At long last, at the tail end of a summer, they found a spot that met all the natural requirements, though the house itself wasn’t quite what they had hoped for.

“This is the place,” the clients told Dean. “We’d like to be in by the spring.”

Dean now had to figure out what to do with an existing structure that posed a host of problems. It had a sort of Z-shaped footprint, the result of many additions. The original structure, a simple ranch probably built in the 1930s, had been variously enlarged and added to: a second floor, ells, a semi-detached combination garage and office. The main house had a small porch and Doric columns made of aluminum. It was, Dean explains, essentially two separate buildings: the main house, and the office-cum-garage, with no aesthetic link between them. “They were like two separate thoughts,” he says.

The buildings had been sited well, however, facing the water and the dock, with a nice pathway to the lake and high-quality plantings. Dean decided he could keep the foundation and much of the original house. Beyond that, though, he says everyone involved—clients, architect, interior designer and builder—recognized that this house was “an opportunity.”

Dean’s design problem stemmed from the many demands he would now have to satisfy. He had to respect the existing site, trying not to disturb the mature trees, stone walls and plantings. “We didn’t want to have to wait twenty years for this to look like part of the landscape,” he says.

He also had to meet the clients’ requirements about the home’s size and number of rooms—and he had to get it all done in time for them to enjoy the following summer in their new place. Having worked at big-name firms in New York—Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, Philip Johnson, and Robert A.M. Stern—Dean is both practical and an “academic architect,” someone who considers the historical context of the site. He doesn’t slavishly reproduce old styles, but he understands and respects what’s come before. The finished house shouldn’t necessarily mimic the architecture around it, but he did want it to look like it fit.

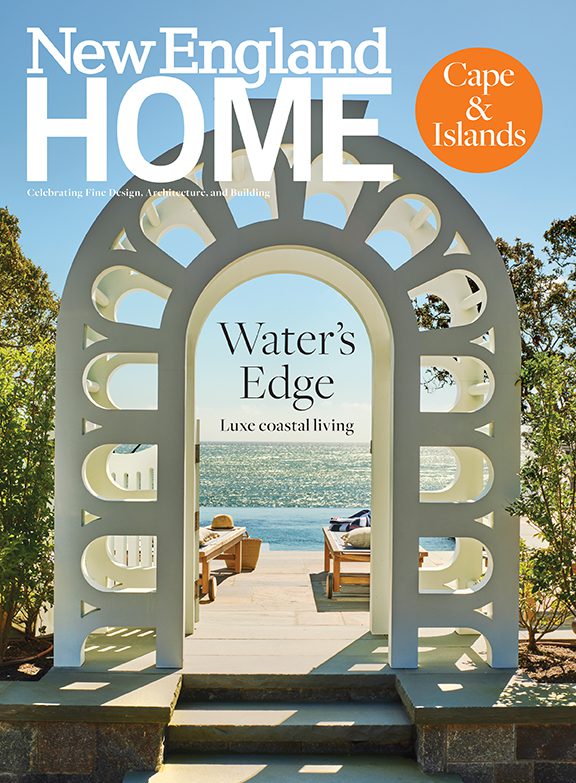

Litchfield County, however, like most of Connecticut, never had much of a lakefront architectural style. Lake Waramaug’s built history consisted of Federal or Greek Revival farmhouses, which wouldn’t translate into an easy, open house for a sports-loving family. Dean and his clients instead looked to the waterfront architecture of other New England areas during the Victorian era, some in the Shingle style, some in the chalet style inspired by Swiss and Scandinavian cottages. “We wanted to tie into the tradition of lake houses that are informal and fanciful,” he says, “but also respect the Connecticut landscape of white frame houses.”

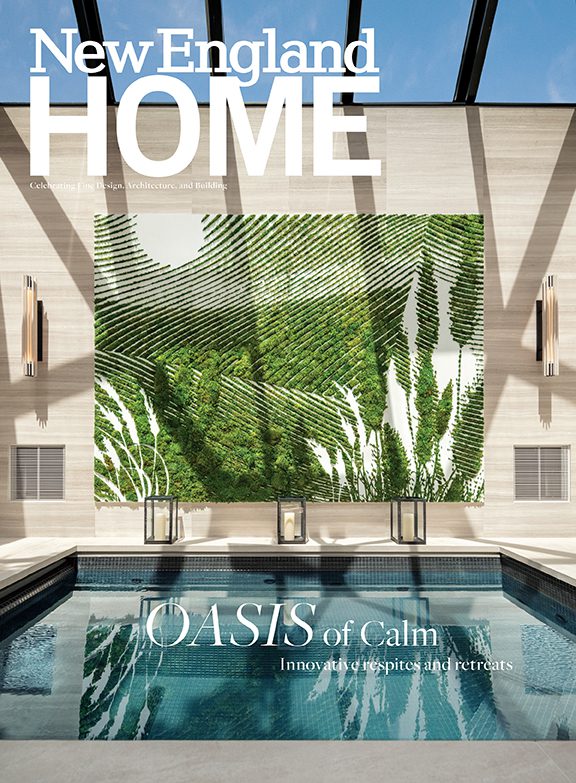

The big design problem, he says, boiled down to, “How do I tie all this together?” If his clients were going to feel calm and peaceful here, he would have to take what seemed like seventeen scattered and conflicting elements, from the dock to the garage, respect the site and the heritage, and somehow create a sense of simplicity. How could he combine all those different elements and turn them into calm?

First he thought, “Porches.” These would create a transition between the interior and the exterior, bringing the outside in and creating semi-outdoor rooms. And big porches fit the architectural style. At present the porches, which are made of red cedar, fir and mahogany, have been treated but not painted, something that Dean says was much discussed. The intent is to let them weather to a silvery gray, he says, connecting the house with the “imperfect natural world.”

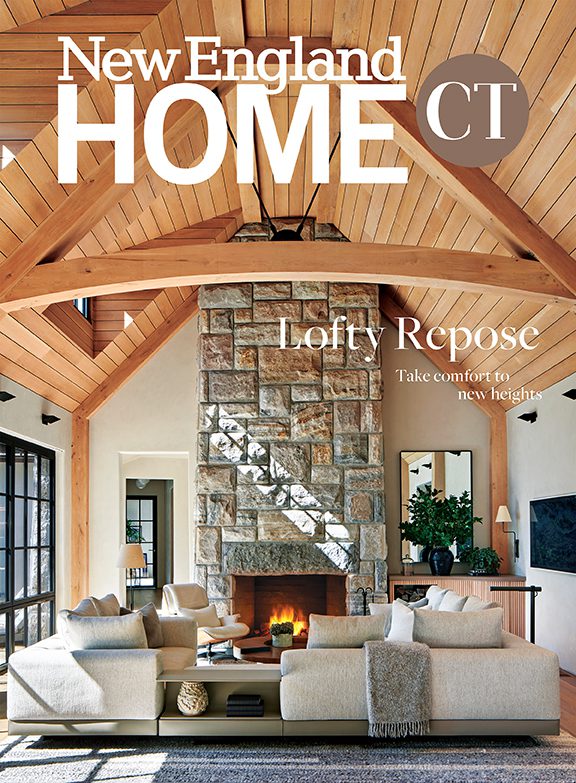

The second part of the solution is what he calls “the big roof.” Rather than a lot of gables and eaves, he put one big lid over the main house and something similar over the adjoining one. Then he adorned the outside with just the right amount of Victorian-inspired details: brackets, gable boards and Asian-inspired fretwork on the railings. That big roof tied the two structures together and gave it a sense of mass.

Anne Miller, a snappy, funny designer from Greenwich, shares Dean’s philosophy: she’s committed not to imposing her particular style, but to making a dwelling that works for the client. She mimicked the water for much of her color palette, and because this was a young, active family, she ensured that the materials she picked were practical, kid-friendly and easy to care for—cotton rugs, big, comfy sofas, nickel finishes and a minimum of accessories. For the porches she picked what she calls “old-style, Teddy Roosevelt wicker.”

Dean’s office handled all the kitchen and lighting design, which he thinks makes the finished product more cohesive. The clients were brave, willing to take the leap of faith necessary to obey the timeline. And the two disparate buildings, now linked, became an advantage: those active kids and their friends have boys’ and girls’ “barracks” (the boys’ room has five twin beds and connects to a mudroom that opens directly out to the lake), as well as a rec room with a pool table. This setup accommodates the constant tide of commotion in and out of the water, while keeping the main house a calm, quiet retreat for adults.

When he looks at the house today, Dean sees a problem solved. It’s a spot full of activity, from the kids and their friends splashing in the water to adults enjoying cocktails and conversation. And over it all, he says, “You get a sense that the house is reaching out of the environment and sheltering it all. It creates a sense of peace.”

Architecture: Robert Dean

Interior design: Anne Miller

Share

![NEH-Logo_Black[1] NEH-Logo_Black[1]](https://www.nehomemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NEH-Logo_Black1-300x162.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.